Feeling Secure or Distant and Anxious? What's happening in your relationship?

Social media has taken somewhat of a liking to attachment theory. There are several versions of what attachment theory is and how to use it in the way we understand ourselves, the people we are dating or are in relationships with. A quick google search will throw up a ton of articles on the ways in which attachment styles of our childhood relate to how we can understand our relationship with our caregivers and significant others.

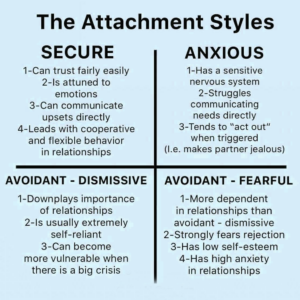

A quick google search will tell you that attachment means “a lasting psychological connectedness between human beings”. There are predominantly four attachment styles born out of experimental observations undertaken first by John Bowlby and then by Mary Ainsworth. The four styles of attachment you will find are secure attachment, anxious/preoccupied attachment, avoidant/dismissive attachment, and disorganized/avoidant-dismissive attachment briefly described from the google image inserted to your left.

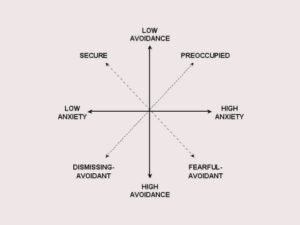

One way that theorists prefer to represent attachment styles is through this graph to your right: A careful consideration of the image to your right shows that we all experience anxiety and avoidance in relationships at different degrees and I would like to add, with different people and at different times. Attachment theory came from observations of children and their mothers. The theory was seminal in understanding ways in which to offer a safe haven and a secure base for young infants and children. Eventually the theory grew to also offer a perspective for adult attachments. It is now commonly believed that as adults:

A careful consideration of the image to your right shows that we all experience anxiety and avoidance in relationships at different degrees and I would like to add, with different people and at different times. Attachment theory came from observations of children and their mothers. The theory was seminal in understanding ways in which to offer a safe haven and a secure base for young infants and children. Eventually the theory grew to also offer a perspective for adult attachments. It is now commonly believed that as adults:

-we tend to experience similar attachment patterns and may experience attachment disruptions that we experienced with our caregivers and

– that we may recreate some of these patterns that cause distress due to developmental delays growing up, causing us to enmesh with our partners rather than differentiate.

-Or that partners lack skills because of these developmental delays leading to unsatisfactory contracting with partners.

Some Insights into adult disruptive attachment, coming from research on attachment theory are that:

- Relationship problems are typically about the “struggle to define the relationship as a safe haven and a secure base” (which means that the relationship is not only a safe place but also a reliable/consistently present place). Families that are made within Patriarchal, capitalistic, cis-heteronormative relationships tend to be a two-person (and a child) unit plus extended family of this unit when available. In situations like this the family unit or the partner becomes the only hope for secure attachment.

- “Isolation, separation or disconnection from an attachment figure is inherently traumatizing.” This kind of distress in partners can leave them responding from a fight, flight or freeze leading to “more automatic, rigid and self-reinforcing” interactional patterns.

- What we want to arrive at is effective dependency. That there is no such thing as over-dependency or true independence. We need to come together to live in an interdependent manner. One which can sustain the unit.

- Sue Johnson, the renowned couple’s therapist speaks about the negative cycles that couples get entangled where “one partner will pursue for emotional connection, but often in an angry critical manner, while the other will placate or withdraw to “keep the peace” or to protect [themselves]from criticism.”

- Depression and anxiety are common occurrences when relational disruptions exist. When partners feel a reeling sense of absence or impending loss of the relationship, they often respond in some typical ways, “These involve…upping the antei, including becoming preoccupied with the relationship, monitoring it constantly and becoming coercive and aggressive; … cooling your jets, including numbing out and shutting down to care less and protect the self, and,… trying both of the above in sequence. The last strategy is used particularly by trauma survivors who have been violated in close relationships and who, simultaneously both desperately need and seek, and also desperately fear and avoid closeness (Johnson, 2002). “

It is important to pause here and reflect on what meanings you are making as you read this. Often, the danger of using such labelled descriptions of relationship and its struggles leads us to quickly start diagnosing, problematising -judging, blaming and shaming ourselves or our partner(s) or even our parents.

Further, queer relationships and relationships that occur in the margins are rare and precious because love in such spaces can feel profoundly scarce. It is important to recognise that queer, disabled, women’s and other marginalised bodies are systemically traumatised. A safe haven and secure base, as you can imagine then is also one that is a privilege. It is important to sit with this awareness that we are ensconced in a system. The ways we experience people and relationship are defined by the spaces that exist around us. This image below really helps me step back and discern the many things I am sitting with when I experience disruptive patterns with my attachment figures.

Global, societal and local communities and cultures impact the way in which we experience safety in our bodies, the way we relate with one another and the way we form attachments. That anxious and/or avoidant ways of experiencing ourselves in relationships tells a story of what our bodies, in a context, has been through. The polarities we feel in our bodies are a result of what we have experienced,. However, our bodies also feel a longing, a longing to experience relationships a certain way. To be with, and to be in intimacy in ways that are joyful. Intercaste, inter religious, queer, disabled relationships exist. These relationships also fall under tremendous strain of a context that impinges upon us a Brahmanical, patriarchal, cis heteronormative, ableist frames. When we engage in our intimate relationships, casting upon one another a normative lens of how our partner(s) must show up we are reacting to a world that wants us to do this and we are also oppressing upon another a way of being they likely have fought or succumbed to their whole life. What would facilitate, attachment theory’s “earned secure attachment”? What would facilitate a way of seeing and being that can truly transform us and help us stop recreating intergenerational trauma?

Stay tuned for our next article that looks at answering this quandary.

References:

Dallos, R., & Vetere, A. (2014). Systemic therapy and attachment narratives: Attachment narrative therapy. Clinical child psychology and psychiatry, 19(4), 494-502.

Fern, J. (2020). Polysecure: Attachment, trauma and consensual nonmonogamy. Thorntree Press LLC.

McLeod, S. A. (2009). Attachment theory. Consultado en www. simplypsychology. org/attachment. html.

-Aarathi