Conversations about neurodiversity are conversations promoting hope

Note: This is a full transcript that was prepared for the TedXIITH talk by Aarathi Selvan.

A fundamental piece of our human tapestry are institutions, especially educational institutions. These are the spaces where we learn and grow profoundly, both with respect to the subject matter of our interest as well as about being human, relating and living in the world. It is meant that transitional and meditative space aiding in our evolution.

Now, if we think of what a regular classroom looks like across age span, desks come to mind. The design of a classroom is such that there is an audience and there is a dias, there are students and there is a faculty member. We sit in rows and learn from a teacher in a closed environment.

A typical student life is one where we come at a particular time in the day and learn a chunk of something at the turn of the clock. So anywhere between 45 minutes to two and a half to three hours is the duration of a typical class at an institutional space. Ofcourse, there will be some variations based on the place you are studying at.

The expectation is to go from class to class, hour after another, switch between subjects and learn between small breaks and lunch times. The student is listening with attention for at least 5-6 hours a day, or understanding a variety of things through a variety of means for long hours, while being present and focused. The student is expected to learn mostly auditorily during class with some visual aids like a PowerPoint and continues to learn after class hours too and perhaps prepares for exams at regular intervals.

There is an understanding that a typical student’s mind functions “normally” and this “healthy” “normal” brain of the student learns best in this environment. In fact, as Nick Walker an eminent scholar in the field of autistic advocacy says, “the understanding of the human brain or mind is that there is one “right”, “normal” or “healthy” way for human minds to be configured and to function and if your neurological configuration and functioning diverge substantially from the dominant standard of “normal”, then something is wrong with you.”

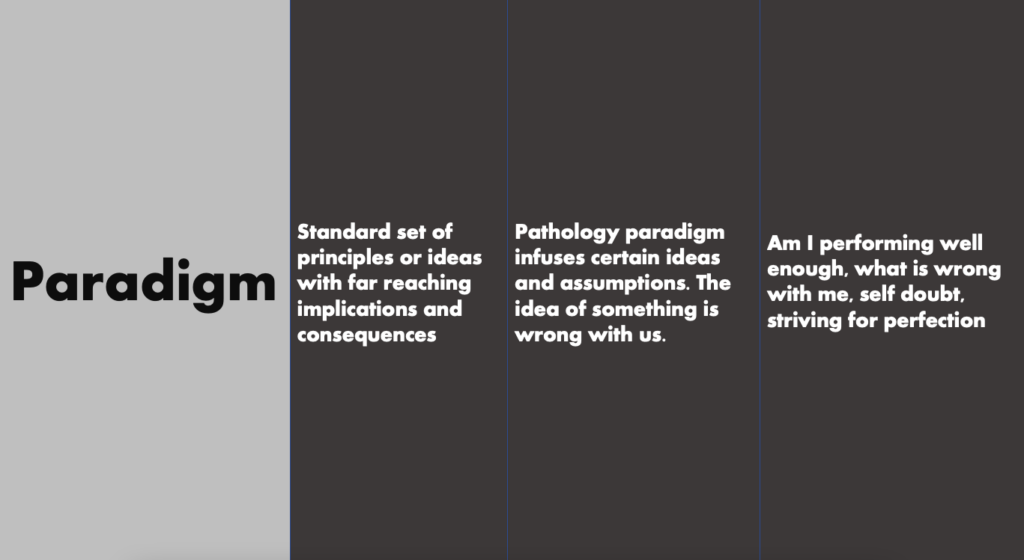

Let’s look at this way of thinking about how our minds must function.This typical way of how “normal” minds function is based on a paradigm of thinking called the pathology paradigm.

Paradigm is a standard perspective or a standard set of ideas. The thing with paradigms is they have far reaching implications and consequences.

Pathology paradigm infuses certain ideas and assumptions in us. So for instance if we are not performing “normally” in our typical classrooms, then we believe that something is wrong with us. We see that the assumptions of the pathology paradigm works inside of us through thoughts of self doubt, the distress around “what is wrong with me”, and our striving for perfection. Assumptions based on a paradigm of thinking shows up not only in how we think our minds and brains function but also how we think our relationships function, our sexuality functions and how success in each field functions. This pathology paradigm finds itself as an outpost in our minds, like the feminist writer Sally Kempton says “Its hard to fight an enemy with outposts in your head”. Thinking that there is something wrong with us never really benefits us. We are constantly doubting ourselves, have I got this right? Am I performing well enough? The list of self flagellation can be never ending.

An important feature of the pathology paradigm is its tendency to look at things in the binary, So when definitions of autism, ADHD, biploar, are drawn out they miss representations that are not typical. Studies have shown that experiences that come under the ambit of Neurodivergence such as Autism, ADHD, and other conditions are underdiagnosed in women, transgender people and people in the global south as well as people of color (Hull et al, 2020; Magaña et al, 2019; Price, 2022; Zhen Li, 2022). Further, studies also indicate that generally adults are underdiagnosed for Autism, LD and ADHD (Shifrer, 2011; Ginsberg,2014; Hull, 2020).

The neurodiversity paradigm on the other hand opens up these rigid representations and binaries, it offers the possibility of getting curious about our diversity. And what is Neurodiversity? Neurodiversity is the diversity among minds, it is a natural, healthy and valuable form of human diversity. These are differences in how we communicate, experience, relate and function in the world.Growing evidence indicates the need to center lived experiences and support self representation as valid (Chapman & Veit, 2020) In this context, I have the privilege of introducing the story of a dear person in my life who has offered their lived experience for us to look at for today’s conversation. Please know this is one story of a self representing Neurodivergent person, and while not everyone’s story, the hope from the paradigm is available to see. Here is an excerpt of Ks experience in their college:

I am K. I am assigned female at birth. Since a very young age, I felt “different” from my friends and there was no language I had access to; to explain why I felt different and masking seemed to be the only option to survive. I aced it so well and nobody suspected anything. For everyone, I was this “normal” girl. Cut to finishing primary education and choosing subjects for 11th and 12th class. I was good at Math in school but not passionate enough to choose Math as my primary subject but did so as all my friends were also choosing the same and I would be labelled “weird” and “not serious” about my life if I chose English or Commerce or Political Sciences. I was a “slow” learner and I struggled to understand Physics. All the competitive exams to get an admission into Engineering are about speed and accuracy. I was accurate but not fast. I hated those 2 years of my life preparing for Entrance exams. The worst for me began when I joined an Engineering college. I hold a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical and Electronics Engineering but those 4 years of Engineering just taught me what a colossal waste of time, energy, money and effort Engineering is if you happen to pursue it because everyone around you is also pursuing Engineering. I never really understood what was being taught in the college and the textbooks. When I had access to the internet and Google-d some of the concepts being taught in the class, I was fascinated by what the Internet had to offer. Tons of YouTube videos (mostly by Professors in the West) explaining the real-time applications of what my books were saying really made me immerse and I was just into reading from the Internet and watching experiments and making notes from them. What this phase of life also taught me is that I am a “slow learner”; it means I need to read everything from the start; I need to have a complete context of what I am reading to understand it. Else I feel distress. The language also needed to be simplified for me to understand and the structure of my degree or the resource material provided allowed for neither which meant I had to read off the Internet. Reading from the Internet also means that you need to read a bunch of articles before landing on that page which explains vector diagrams in the simplest way possible. This takes a lot of time and I was always “lagging”. I had a perfect understanding of things but by the time I caught up with my classmates, (who were rote learning to pass exams or in some cases, some of them actually understood things pretty quickly) I was still “lagging”. The problem with all of this is – what needs to be completed in a semester that lasts for let’s say 5 months, I needed an year to understand the entire course and obviously the education system didn’t allow for that. I always experienced a lot of distress, unable to figure out why I was not able to grasp things quickly; afterall I was a good student in school who was tagged as one of the brightest students. Did I have a learning disability? I was terrified at this thought that it could be a learning disability because the ramifications of that meant the people/society around me would say “I am not fit to do something”, “I am making excuse and not trying enough” or that “I am lazy and inattentive and using LD as an excuse because it never showed up in school” .

The 1980s and 1990s saw a new wave of understanding of the human mind and brains. This caused an acute paradigm shift in large pockets of humanity that began to explore Neurodiversity. The neurodiversity movement was led by Autistic folks and represents the voice and lived experience of neurodivergent people.

When we are distressed by the normative student spaces and voice this distress, we hear that everyone experiences similar distress and that all that is needed is to trudge along and keep pushing oneself. While this may be wise advice for some, a neurodivergence affirmative stance, in institution settings can be liberating for all. A neurodivergence affirmative stance is one that is informed by the historical understandings of structural inequities and the unique life stressors and nuance in neurodivergence.

What is the vision of a neurodivergent affirmative educational space?

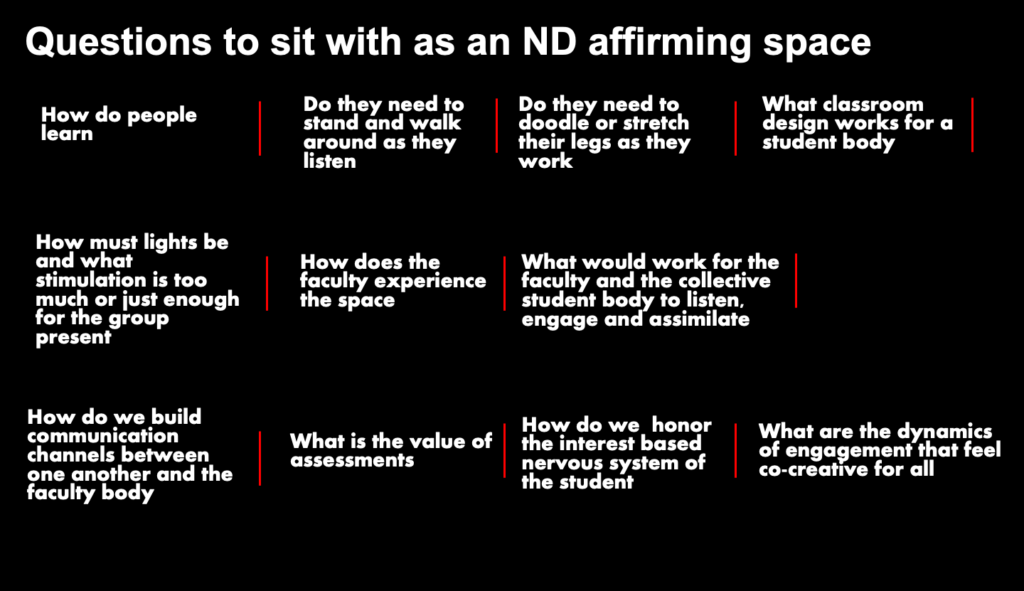

A neurodivergence affirmative space is curious about the student body present in a given time. As a mental health practitioner, teacher and supervisor for undergraduate and Masters students as well as new professionals in my own field, this stance leaves me with questions like: how do people learn? Do they need to stand and walk around as they listen? Do they need to doodle or stretch their legs as they work? What classroom design works for a student body, how must lights be and what stimulation (noise, smell, visual, kinesthetic and touch based stimulation) is too much or just enough for the group present? How does the faculty experience the space? What would work for the faculty and the collective student body to listen, engage and assimilate? How do we build communication channels between one another and the faculty body? What is the value of assessments? How do we honor the interest based nervous system of the student? What are the dynamics of engagement that feel co creative for all?

A neurodivergence affirmative space is curious about the student body present in a given time. As a mental health practitioner, teacher and supervisor for undergraduate and Masters students as well as new professionals in my own field, this stance leaves me with questions like: how do people learn? Do they need to stand and walk around as they listen? Do they need to doodle or stretch their legs as they work? What classroom design works for a student body, how must lights be and what stimulation (noise, smell, visual, kinesthetic and touch based stimulation) is too much or just enough for the group present? How does the faculty experience the space? What would work for the faculty and the collective student body to listen, engage and assimilate? How do we build communication channels between one another and the faculty body? What is the value of assessments? How do we honor the interest based nervous system of the student? What are the dynamics of engagement that feel co creative for all?

We may know of accessibility accommodations for Disabled folks in institutional settings, and while it is important to make those accessibility accommodations possible, what would it be to do this not as an afterthought but as a forethought as we begin to design spaces and learning needs? Embracing neurodiversity as the paradigm, offers individuals in space opportunities to get curious about what it means to learn,engage and communicate in ways that work for everyone’s nervous system.

Here is the rest of Ks story:

When I reflect on everything that I experienced during my undergrad life, I now have a fairer understanding of what was. I did not have a learning disability nor was I a slow learner. I just learnt differently. My needs were different. My brain is wired to function a certain way and the institutions that I was a part of never factored my needs while designing the course structure. I am more of a visual and kinesthetic learner and would understand and learn if I saw, touched and felt the different concepts that were in these Engineering text books. Sometimes I wonder why I understand “angle of banking” which was taught in school so well but never understood “phasors”. Fortunately my school teachers would demonstrate the concepts and its applications in real life with examples. I wish that was the case in Engineering too.

More than that, I wish someone would have told me about neurodiversity and that everyone’s brain is not the same; I have been told for almost 28 years of my life – “Everyone has the same 24 hours and everyone is gifted with the same brain; it’s all about how you use them effectively and efficiently”. Today as I embrace my neurodivergence, I can say it is rubbish and oppressive to think everyone is gifted with the same 24 hours and the same brain. Different factors can contribute to a problem, and it’s unfair and unhelpful to dismiss someone’s feelings by giving them general advice and calling it motivation. Understanding neurodiversity and my own neurodivergence has been liberating to say the least. I don’t see myself as a problem anymore when I don’t get around to finishing things in a timely manner as others. Instead I am exploring my ND and ways to navigate it in a way that does not feel like a burden to myself or others in a relational setting. Everytime there is a “struggle” for me while others seem to be able to do things, I get curious about what the “struggle” is about and what story is coming up when I lean into my difference and the resultant embodied experience of accepting ND has been truly satisfying. My journey has just begun and I have a long way to go. I am realizing neurodiversity is not a linear trajectory and there is a lot of intersection at play. Regardless of what my career choice or lifestyle choices are, even if chosen based purely on my interests and passion, there is still neurodivergence present which will show up and I hope to understand and embrace the complexity that is the human mind and not problematize myself as “why am I different and when will I ever feel fixed. Reading about ND and having a safe space to have conversations with a community of like minded people also helped me comprehend ND in a very non-medicalized/pathologised fashion and what stands out to me is that neurodivergence self-advocacy is as valid as any other diagnosis.

In the words of autistic author and educationist Nick Walker “There is no”normal ” or”right ” style of human mind, any more than there is one”normal ” or”right ” ethnicity, gender, or culture.”

As a teacher and supervisor in adult learning spaces some of the ways in which I am learning to be neurodivergent affirmative is by starting conversations by exploring people’s hopes for the teaching space they are in. I also share my stance towards my work, and my hopes from the teaching space. There is no expectation for anyone to have explored neurodivergence. My first session usually starts with community agreements where I ask these questions about what our learning space must embrace to make it a generative experience, and as a group of people we document them. This becomes a live document that can be added to anonymously and is made available for everyone to access. I commit to revisit this document and I ask for support to remind me to visit these agreements at assigned intervals during the course of my time with people.

We work on ideas of being self-responsive, that is, to get curious about what is happening for oneself while in the space and honoring that, some ways might be to use the phone to regulate when overwhelmed, doodle, draw and eat when listening, and sitting beside folks that dont feel dysregulated by this, stepping away and taking breaks not only at pre-determined break times but also when there is group consensus at other times. And committing to having study partner(s) to support one another’s learning experience if that is preferable.

With respect to space design, given white tubelights can be hyper stimulating, based on group consensus we may use warmer lights or lamps . Fidget toys/stimming tools made available for those who need to stim.

I also have discussions with the class at regular intervals about the various ways we can learn and seek to see if people have more ideas and continue to learn on my own too on what else I can do.

This is not the “right” way to do things, remember we are trying to move away from such binaries, I find that at this given point in time, this works in my teaching spaces, I’’d like to continue to stay curious.

In my work as a mental health practitioner who consults with people, we practice listening to our bodies, to get curious, to discern how we process and function in the world. Some things we may try to discern as an example can include – the exploration of both the distress of social anxiety and what else it can be, such as perhaps the over stimulation from peoples presence and noise and more. Another example could be of a person experiencing depression; we explore the pain of depression and more, like perhaps it’s our body’s protest to harm done upon us individually and collectively. We explore the suicidal ideation and if there is more, such as the workings of the pathology paradigm pushing us to death over life in the conditions presented to us.

My invitation is to get curious. We have for so long been riddled with self-doubt and all its close friends – guilt, shame, self-criticism and others. How can we visibilize ourselves and others, honor pain and embrace the richness of our minds? .

A neurodiversity paradigm is the nurturing of a just society. I’d like to end with what Baba Sahib Ambedkar says about a just society:

“A just society is that society in which ascending sense of reverence and descending sense of contempt is dissolved into the creation of a compassionate society”

Conversations about our bodies, minds and society is a conversation for all, including all stakeholders of learning spaces. The Rehabilitation council of India indicates that more than two million autistic people in India, yet there is little conversation about neurodiversity. I believe that When we are aware of Neurodiversity, and center the fact that all brains are natural, healthy ways of existing in the world, we can finally rest the mantle of shame and all the questions around what is wrong with me or you,and begin to hold space for each other and ourselves to make conversations open hearted, to collectively unfold into a compassionate society.

-Aarathi.