You’ve probably heard many people use this term. You’ve probably heard it from feminists of minority backgrounds calling out for the need of intersectionality in feminism. And you have wondered about it. What is intersectionality? Is it just another fancy feminist jargon? Today, we discuss intersectionality, its history and context and the dire need for it in today’s world.

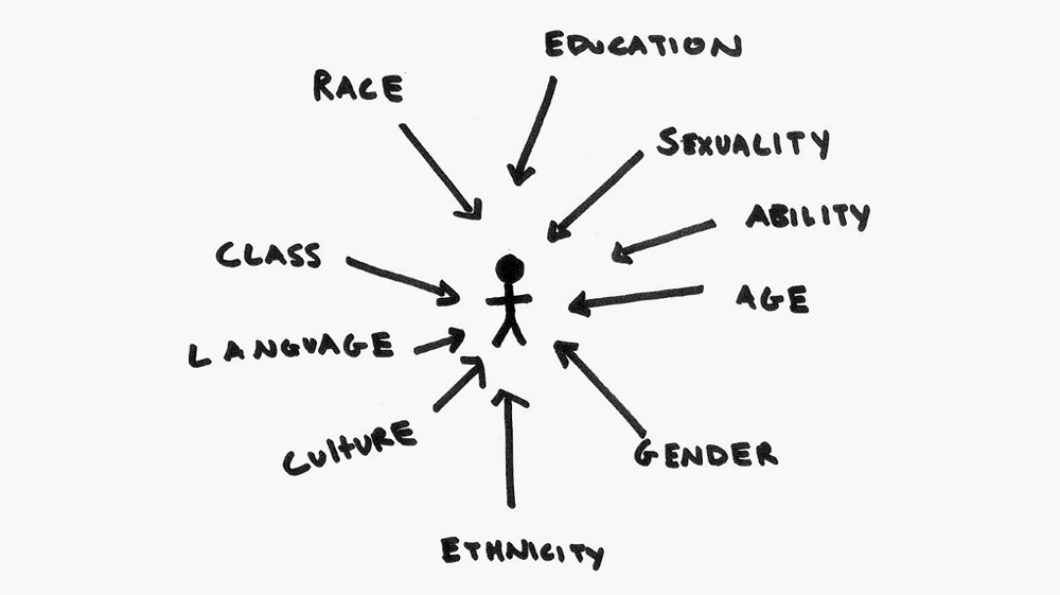

Intersectionality is a paradigm that addresses the multiple dimensions of identity and social systems as they intersect with one another and relate to inequality, such as racism, genderism, heterosexism, ageism, and classism, among other variables (APA, 2017b)

In the year 1989, Kimberle Crenshaw introduced the term, “Intersectional Feminism.” She is a Black feminist and lawyer (And also the Professor of Race and gender at UCLA School of Law and Columbia Law School) who wanted to bring to everyone’s attention about the oppression black women face: not as women and not as black, but because they were both black and women. That is what intersectionality is about: how different aspects one’s identity (religious, gender, class, sexuality etc.) influences the discrimination one faces. It is, essentially, about the people who get lost in-between. At the juncture of wanting equal rights as black people and women, black women often got lost. The discrimination black women face is different from the discrimination white women face.

Intersectionality is realizing that you have more than one identity. Your identity is the culmination of all these aspects: your race, gender, your language, your class, your sexuality. It’s never just that you’re a woman. These identities cannot be singled out, because we all cannot be kept under a single box.

INTERSECTIONALITY IN INDIAN CONTEXT

To understand intersectionality in India, we have to first understand the diversity of India. We all know how diverse our country is. With twenty-nine states, all of which have their own language and culture, India stands as a highly culturally diversified country. All these twenty-nine states have different struggles. Groups under these states have had different experiences.

For example, people in North India have different struggles than people living in the South. This is, of course, a generalized statement for better understanding. And precisely this is the reason that the westernized idea of feminism will never work in India. We face different issues that need a different model of working.

QUICK HISTORY OF FEMINISM IN INDIA

The feminist movement in India started in the 1850s by men who wanted to uproot evil traditions like sati and child marriage. In the 1900s, the nationalist movements started to focus more on the freedom of India than these social issues.

However, Dalit women have been active throughout history, though often this has not been recorded. They were actively involved in the anti-caste and anti-untouchability movements in the 1920s. Mainstream feminist thought in India during the 1980s and 1990s began to recognize issues surrounding caste. This was a marked change from the various feminist movements in the 70s and 80s which did not address caste issues.

Intersectional Feminism, even before the term was coined, was practiced in India by two pioneers called Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule in the nineteenth century.

Jyotirao Phule was an Indian thinker and activist who advocated for women’s rights and was against the caste system and untouchability. He knew that women and the lower castes were very disadvantaged in the society and understood the importance of education to emancipate them. He, along with his wife Savitribai Phule, started the first school for lower-caste girls in Pune. However, they soon faced backlash from the Uppercaste community who thought it to be a sin. His father expelled both of them from his home.

They moved in with a friend whose sister, Fatima Sheikh, knew how to read and write. And the two women, Savitribai Phule and Fatima Sheikh, challenged these notions and started a school in 1849. In 1852, there were three Phule schools in operation 273 girls were pursuing education in these school but by 1858 they had all closed due to the First War of Independence. Their joint efforts led to the democratization of education rights that we see today.

It was in 1949, when the Constitution was drafted that equal rights were given to all citizens in India. Babasaheb was a fierce advocate for equal rights and is seen in the way he publicly burnt the Manusmiriti, a patriarchal and misogynistic religious text.

He facilitated for the legal recognition of women as equal citizens. He granted women the right to divorce, the right to inheritance and he provided for legal recognition of inter-caste marriages. And he did this despite the opposition he faced from the conservative members of the Congress Party.

UNDERSTANDING LAYERS OF OPPRESSION

There’s no denying that oppression does not exist. However, oppression is not a one-size-fits-all scheme. Different groups are oppressed differently. When we speak of intersectionality, we have to remember that minority groups are not oppressed more. Women in minority groups are not oppressed doubly than women in majority groups. They’re oppressed differently.

Crenshaw explained, “The way we imagine discrimination or disempowerment often is more complicated for people who are subjected to multiple forms of exclusion. The good news is that intersectionality provides us a way to see it. We might have to broaden our scope of how we think about where women are vulnerable because different things make different women vulnerable.”

Intersectional feminism aims to highlight this. The fact that women from different groups are oppressed differently. Dalit women go through different struggles than their Upper Caste counterparts. While UC Women might fight for equal pay, menstrual hygiene etc., Dalit women fight for these rights but with the added layer of fighting caste-ism and fetishization of minorities.

While Muslim women in India have different struggles altogether. Their struggles can include fighting the sexism in their community and outside the community, objectification of their Muslim identity, and very recently, their fight for Citizenship (in the recent Citizenship Amendment Act).

However, this doesn’t mean that Muslim women are the most oppressed. It means that feminism has to be completely aware of the social inequalities in the structure of the society. Once we see this and if more people understand the privilege some have over the others, then we can truly be anti-oppression. Oppression is not a competition based on the degree of who is more suppressed in the society. We need to understand these oppression as a unique they are in their own contexts.

Understanding Privilege

One of the most important aspects of intersectionality is to understand one’s privilege in the society. It is not as easy as it sounds because it means that we have to learn how to understand our position in society and to question authority. Intersectionality is about this. As a Muslim woman, I still cannot deny the class privilege I have. My identity as a Muslim Woman is not independent of the fact that I come from a upper-middle class family who has never had to go through the issues other women of the society have had to go through.

When we recognize privilege, we understand the society better and also are in a better position to help people. This comes from constantly challenging authority and people in positions of power. Once we unite against the common enemy we have, that is, patriarchy, only then can we fully see equality and equity.

And as Audre Lorde said, “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.”

Audre Lorde, June 1981

—

Further Reading

Is Mental Health Political?

On Identity and its Erasure

Omaiha Walajahi

Writer

Pause for Perspective